I’ve got this casual infatuation with eggs. I love them, actually. Their off-ness, the way they roll on a counter, the way they ooze and crackle in a pan, how they thicken or poof a dish. Eggs are cheap meal, they can be decorated, pickled or thrown. But I had never learned how to make the most beautiful of eggs, a perfect boiled parcel of gooey-goodness: a poached egg. Eating them feels rich, decadent, covered in hollandaise or cooked in a homemade tomato sauce.

Last summer on a trip home to Minneapolis, I called up my go-to egg aficionado, my mother’s mother, Grandy. She’s oddly egg-like, actually. Taupe-y, almost. She has a lot of beige and white in her aesthetic, the kind of blue button-up wearing woman who still has my great-grandmother’s sewing kit equipped with thimbles in her bedroom closet. She’s always been the most domestic of my family members. My mother loves to cook and entertain and vacuums and windex-es before the cleaning lady shows up. Myself, I dabble in organizing rooms, folding fitted sheets and making pasta salads, but Grandy—she is the archetype, the mother figure. I’ve always assumed the trait has slowly sifted out of the Seiverson line, that if home-making activities are something I’d like to pursue, it’s in my blood, but needs to be excavated.

Grandy’s got it in her genes, which she hang dries in the basement then irons on a small Ikea fold out on her bed. She makes me want to learn to quilt. When I was still a kid, I used to spend the night at her old place on the Mississippi and we’d watch “The Little Rascals” and sing about pickles and dollars.

|

| Source | Andrew Filer, Flickr |

In the morning we’d wake up to barely browning english muffin toast—this magical hybrid, airy like Thomas’ but not dense and chewy—and eggs fried quickly in too much butter. Sometimes she whipped up coveted egg-in-a-basket, a small window cut out in the toast with the bottom of a juice glass, the perfect frying hole for a small egg. Sleepovers at Grandy’s were the only times I would eat breakfast. My own mother would force me to drink Carnation Breakfast Essentials, a disgusting ‘chocolate’ protein ‘shake’ that tasted like saw dust and cold Swiss Miss.

“Mom, this stuff makes me gag. I’m going to barf all over the bus and no one will talk to me.”

“Well, Hun, we’ll just have to home-school you until you start eating real breakfast.”

But I could stomach Grandy’s eggs. They didn’t have the cold, soggy features I had associated with breakfast. They warmed me, got me going. I began cooking eggs on my own. Julia Child taught be how to make a French omelet—it’s in the wrists—I found I like my scrambled eggs barely cooked, as cloud-like as possible. I made the Barefoot Contessa’s quiche Lorainne, which, let’s be honest, contains mostly cream, not eggs. But I suck at poaching an egg.

I told myself the simplicity makes dropping eggs into boiling water so difficult. You can find tricks and secret techniques all over the internet, but none of them seemed to work. The number of eggs I wasted, yolks bursting in bubbling water, egg whites turning into a bland egg-drop soup, has to be at least two dozen.

Grandy had the answer.

“Oh Han, I’m flattered you’d ask me. It’s easy, Sweety, come over on Saturday and I’ll show you.”

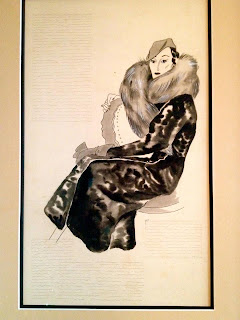

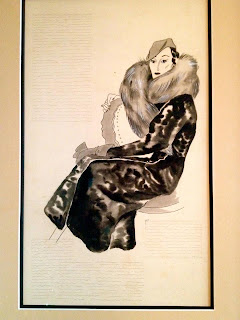

We stood in her kitchen, surrounded by heart-shaped black and grey stones she had collected on the Mississippi and on the shores of Lake Superior. Her spatulas a heart-shaped. She has framed drawings her mother made in the 30s—my great grandmother drew the fashion designs for Vogue before cameras were commercialized. I never knew my great-grandmother. She had died very young, when Grandy was only nine. On the counter we gathered a small, 2 quart pan and filled it halfway with water, a tablespoon of vinegar, a slotted spoon, some salt and two slices of english muffin bread. We were listening to Etta James.

|

| One of my many failed attempts at poaching |

“You’ve got to get the water just barely boiling,” Grandy said, pouring the vinegar into the pot. “Bubbling up the sides. It can’t be too hot or they will break.”

“Did your mother ever teach you how to cook Grandy? Was she a good cook?”

“Oh, she was a beautiful cook. Everything she did was beautiful—she was an artist. And she cooked like one. The day she died she left meat out, defrosting on the counter.”

A few months before my Mom had told me Grandy was writing an essay on her mother’s death and how it had affected her life. At twenty I still didn’t know my family history beyond two generations.

“Grandy, will you tell me about her?”

As the water heated up, when it was just right, she swirled the pan slightly with her wrist so that the liquid spun in a circle.

“I don’t know much, Han. I was so little. So, so little. She made all my clothes—she loved sewing. I hated it. I wanted the clothes from the store, but all mine had perfect little buttons and pockets.”

“But how did she die?”

She tapped the egg on the edge of the counter, held the cracked vessel over the pan, pushed her fingers through the shell, and lowered the gloppy mass into the eye of the tornado.

“She left a note one afternoon. I was at girl-scouts. When I got home, my father was on the steps. He told me the neighbors had invited me over for dinner. It was like she disappeared, it never felt like she died.”

If your egg looks awful at this point, like an old man with a beard floating on his back, you’re doing it right.

“In her note she said she couldn’t be the wife and mother she ‘ought to be.’” Grandy said. “I didn’t know any of this until much, much later, when I was 16 and my step mother died suddenly, when I put the pieces together.”

Poaching takes patience. As the filmy strands of egg become opaque and less flimsy, gather the whites with the slotted spoon and tuck them loosely around the yolk.

I watched how Grandy made the egg into a neat little bundle with ease. On cue the bread popped up from the toaster.

|

| A drawing for Vogue by my Great Granmother |

“She was before her time, Hannah. You couldn’t do this. You couldn’t make eggs and be an artist.”

She handed me the butter for the toast.

“You had to choose. She wasn’t domestic enough. Wasn’t a mother enough. Cared about her own art more than her children.”

She set the poached egg on its toast bed.

“Of course now we know that’s not true. She just wanted more than she was given. She wanted to get out.”

I salted and cracked pepper on the tops of both the eggs. We sat down at the dinning room table. It was before noon and the sun was just reaching the tops of the Minneapolis skyline.

“Thank you for telling me, Grandy”

“I could’ve told you sooner. We should know these things about each other. Share ourselves.”

She lifted the butter knife over our breakfast, and sliced, letting all the insides out.