Wednesday, June 12, 2013

Monday, June 3, 2013

The Finishers: Overnight at Sweetwater's Donut Mill | Rough Draft

A single bell chimes, reverberating through the empty shop. Ceramic coffee mugs, 30th anniversary travel thermoses and plush bears with dopey faces look down from their perches, sitting high above the glistening glazed donuts.

At 3:12am, a magenta truck pulls up to the drive-thru. His face obscured by shadow, a forty-something wearing a trucker hat nudges his scruffy chin out the window, his voice full of sleep.

“Gimme two Bostons.”

Mary Schwarts knows this regular. He’s part of the night-time crowd, the ones just ending their days closer to dawn than dusk. Three or four times a week she works the night shift, 10am-6am, filling 170 dozen boxes of donuts for the morning pick-up, re-stocking over fifty flavors all while working the counter and the drive-thru. She’s gotten good at it after working at eight different donut places, but she says Sweetwater’s is the best of them all.

She climbs a salmon-colored step-stool covered in crumbs—donut carnage—and reaches for the Boston creams on the top shelf.

“Hey hon, I’m sorry” truck man said, “I forgot my wallet. Gonna go.”

Mary doesn’t hesitate. She stuffs the donuts into a single waxy bag.

“You can pay tomorrow. We know you’re good for it.”

Sweetwater’s Donut Mill opened in Kalamazoo in 1983 on Stadium drive and quickly added two additional locations over the next six years. They’re known for their classic treats, both yeast and cake varieties, but they also have famous apple fritters, Piña Colada muffins, a pistachio muffin that looks like the Hulk is bursting forth from it’s neon-batter insides, cherry cordials and hundreds of donut holes. While their local ingredient, all-from scratch recipes attract the masses, their 24 hour service keeps the place breathing while the rest of the city sleeps.

During the day, the donut mill fills with flocks of hungry visitors. But overnight, a select group makes their way to the haven of fried goods and cheap coffee. Late night custodial workers, truckers, pizza and Jimmy Johns delivery guys, pregnant women, Western Michigan University and Kalamazoo College students, high kids from Menna’s next door and regulars who come in every night for a quick chat and a long-john mill in and out, and Mary knows all of them.

“I don’t know why, but I know when to say good morning to someone and good night to another person. You learn how to read people.”

At 2:12am, a guy walks in wearing a “You Mad, Bro?” T-shirt, camo shorts and a Detroit Tigers hat, followed by a larger guy with a buzz cut and baggy jeans and a sweatshirt that says “Roll me a fatty” on the small of his back. The first orders a grasshopper, a new flavor, neon-mint colored and flavored frosting with a coating of chocolate chips and chocolate drizzle atop a chocolate cake donut. The second, two sugar raised.

They sit on the park bench seats next to the windows for a second before deciding to take the donuts to go.

Mary wipes her hands on the front of her Sweetwater’s Western shirt. She got it as a gift last year from the shop so that she could promote both the University and the donut mill. She tucks her dark hair back into a bun with a thick black head-band keeping her bangs back. Her shimmery purple eye shadow glimmers like the four diamond studs on her ears. The thick stitching on her jeans matches the powdered sugar donuts.

“I’ve been wanting to try this one.”

Mary grabs a raspberry jelly frosted with white fluff, rips it in half and bites into the filling.

“It’s just okay,” she said, taking one small second bite from the cake before throwing both halves in the trash.

Mary says working alone at night gets exhausting. Between 10pm and 6am she’s the only one working the front of the house. There are usually two or three people working in the back, a cleaner and a fryer. The finishers, the ones who glaze, frost, sprinkle and stuff the donuts don’t get in until later, around fiver or six in the morning.

She also works at Tim Hortons and attends Western as a full-time student studying to be a teacher in Family and Consumer Science—the updated version of Home Economics. Her favorite donut had been the chocolate cloud, a yeast donut filled with white fluff and a chocolate glaze, but has recently been replaced by the s’more, a chocolate cake donut topped with marshmallow fluff and a graham cracker sprinkle.

Ron, the cleaning guy wears a weight bearing belt to help his crooked back. His handle bar mustache and pony-tail dangle over the sink. He’s pissed someone left mop water in the back and yells something to Mary, but she just shrugs.

“Everyone is really great, but midnights bring out a lot of creeps.”

Mary usually feels safe, and emphasizes that she’s never felt vulnerable at the store, but sometimes she feels uncomfortable.

“This one guy, I think he watches girls on his computer while he’s in here, but I’m not sure. People are nice but they leave and you’re like holy crap, this guy could abduct me.”

Mary doesn’t want to talk about it, but she does think the sexual attention she gets in the store gets really old. A customer who comes in playing with an orange lanyard asks her teasingly if she likes bananas. She has a consistent defense, a quick eye roll and then asks if they’d like coffee.

“I take advantage of being the only girl so much.”

Ron comes back out from the back. No one has entered the store for awhile, but the door chime still hums slightly. Ron walks over to the sink next to the ‘90s cappuccino machine.

“Whatcha doing? Washing your hands?”

Ron shrugs and dries his hands on a brown paper towel.

“We don’t do that kind of thing here” Mary said before turning around to refill the buttermilks.

“But I’m kidding of course.”

Word Count: 1016

Intended Publication: Second Waves or a Kalamazoo branch of Maggie Kane's overnight radio series.

Wednesday, May 29, 2013

Show and Tell | Story Corps, Dawn Maestas

For my show and tell, I knew I wanted to share something from Story Corps. I've been following Story Corps for awhile now since I first heard one of their stories broadcasted on NPR. Their tagline is "every voice matters" and the subhead on their NPR page is "sharing and preserving the stories of our lives." Sometimes the stories highlighted are stunning, heart-shifting narratives. Other times I get bored. But for the most part I'm a huge fan of the organization's work both as a non-profit and as talented, thoughtful story-tellers.

The story I've chosen is one I heard recently over the radio. The article, "Tattoo Removal Artist Helps Clients With Emotional Scars" was written collaboratively, which aligns with the organization's mission. I think this accountability is what attracts me most to StoryCorps stories—not all of the pieces are social-justice-y, but their mission is clear and widely noted:

We do this to remind one another of our shared humanity, strengthen and build the connections between people, teach the value of listening, and weave into the fabric of our culture the understanding that every life matters.

This, to me, is both cheesy and essential. It makes it easier to see the 'why' in the profiles we just wrote, and why I like some of the pieces more than others. The StoryCorps works that don't fully incorporate that 'why' are the ones that bore me, but this piece about Dawn Maestas, a tattoo removal specialist and survivor of domestic abuse removes tattoos for women who have been forcibly tattooed or who's tattoos reference or remind them of their abusers. It's much shorter than many of the pieces we've read or even the one's StoryCorps normally produces, but I also thought that was a fun test, to see if this fits in the realm of 'narrative' pieces.

StoryCorps is an independent nonprofit organization whose mission is to provide Americans of all backgrounds and beliefs with the opportunity to record, share, and preserve the stories of our lives.

|

| Dawn Maestas |

We do this to remind one another of our shared humanity, strengthen and build the connections between people, teach the value of listening, and weave into the fabric of our culture the understanding that every life matters.

This, to me, is both cheesy and essential. It makes it easier to see the 'why' in the profiles we just wrote, and why I like some of the pieces more than others. The StoryCorps works that don't fully incorporate that 'why' are the ones that bore me, but this piece about Dawn Maestas, a tattoo removal specialist and survivor of domestic abuse removes tattoos for women who have been forcibly tattooed or who's tattoos reference or remind them of their abusers. It's much shorter than many of the pieces we've read or even the one's StoryCorps normally produces, but I also thought that was a fun test, to see if this fits in the realm of 'narrative' pieces.

Wednesday, May 22, 2013

The Events of October | Reading Response

In chapter seven, "Hold Fast," the first chapter after the murder-suicide takes place, Gail enters the story as a character, listening to President Jimmy Jones speak to the campus, choosing to discuss gun-control as a cause of the act, instead of violence against women. Here, Gail's authority wields the story, as she retrospects, and stated "At this moment the struggle began over how this story would be told" (139). She's speaking of how Neenef would be seen as a murderer, as a loner, a 'foreigner,' as someone who had gone mad—Maggie, his victim. How the media would construe a story that was easier to tell. How the media—we, journalists—have the opportunity and the obligation to tell a story the way we believe it should be told.

This was a very tough read for me. For the past four years, I've harbored some shame for not having read 'the book.' I remember my first year seminar, barely four weeks into the quarter, walking from Trowbridge to Humphrey House for Di Seuss' Spread the Word: Poetry in Community class. I think I accidentally went to the community reflection. Maybe a friend asked me to go or I was just meandering around, wasting time before my 11:50. But I remember one of my new seminar friends crying in one of the back pews, weeping over the story of Maggie Wardle and Neenef Odah, and I remember feeling selfish for crying for myself. At that point I had very little knowledge about violence against women, and what I had learned seemed very external, detached from my own experience.

Four years later, this past October, I attended Gail's talk for the third and last time. I missed her second to last talk my junior year when I was abroad during the fall. As a senior, it's frightening, sickening, for me to realize how different my views on violence against women, particularly within the context of our campus have changed, knowing now how my friends, my family and I personally have been affected.

I'm interested to hear how others interpreted this text. I had to take countless reading breaks. My housemates have been worried about me the past couple days as I've churned through the book. I regret not reading it slowly, but the way Gail has crafted the text, I think she meant for it to pile up, for everything to get compounded so that you can't stop until you've finished.

A quote on page 117 stuck with me throughout the reading, that I had to keep referencing back to in order to remind myself of why we're reading such a difficult, grievous text.

This was a very tough read for me. For the past four years, I've harbored some shame for not having read 'the book.' I remember my first year seminar, barely four weeks into the quarter, walking from Trowbridge to Humphrey House for Di Seuss' Spread the Word: Poetry in Community class. I think I accidentally went to the community reflection. Maybe a friend asked me to go or I was just meandering around, wasting time before my 11:50. But I remember one of my new seminar friends crying in one of the back pews, weeping over the story of Maggie Wardle and Neenef Odah, and I remember feeling selfish for crying for myself. At that point I had very little knowledge about violence against women, and what I had learned seemed very external, detached from my own experience.

Four years later, this past October, I attended Gail's talk for the third and last time. I missed her second to last talk my junior year when I was abroad during the fall. As a senior, it's frightening, sickening, for me to realize how different my views on violence against women, particularly within the context of our campus have changed, knowing now how my friends, my family and I personally have been affected.

I'm interested to hear how others interpreted this text. I had to take countless reading breaks. My housemates have been worried about me the past couple days as I've churned through the book. I regret not reading it slowly, but the way Gail has crafted the text, I think she meant for it to pile up, for everything to get compounded so that you can't stop until you've finished.

A quote on page 117 stuck with me throughout the reading, that I had to keep referencing back to in order to remind myself of why we're reading such a difficult, grievous text.

"In many ways, the story of this night is about what the mind cannot grasp. Memory is a trickster in any case; in such a case as this, memory shattered by trauma struggles to piece together a logical story and often comes up with conflicting narratives."I think reading this text, written by a professor I know, which takes place at my home, with characters who I still interact with and seeing letters from the president, just like the ones we receive weekly from WO today was a strong lesson in place. As I read the book, I realized the magnitude of Gail's investigation, how many people she must have spoken with, how many hours she must have spent reading IM messages, campus emails, talking to grieving parents. Writing our profiles felt like a lot of work. Taking on a project like Gail seemed unfathomable, and I'm sure it took an amazing toll on her as a writer, a professor and a person within the K community, but seeing how she crafted these narratives makes it much clearer to me why this type of writing in necessary and creates a space for movement and change.

Tuesday, May 14, 2013

Alison Wonderland | Second Profile Review

Hey all. Disclaimer: This is a very minimally revised piece. My interviewee was unable to meet this weekend and only performs on Wednesdays (perf DOGL timing) so I will have a more updated piece with snippets about Alison performing as well as bits from her regulars/customers/fellow staff. The heft of what I’ve updated is her physical appearance early on and scattered throughout the piece, plus a few images. Happy DOGL!

Alison Cole needs a kazoo. This Wednesday at the Old Dog Tavern in Kalamazoo Michigan, Alison plans to sing and play a solo to Hall & Oats' hit "I Can't Go for That (No Can Do)."

Her old kazoo went missing and she’s hoping to buy a new one, preferably one that says “There really is a Kalamazoo.” She considered where she could find one downtown while eating a tempura shrimp roll with crab on top from D&W. She mixed a heaping soup spoon full of wasabi into her gluten-free soy sauce until it turned the color of March sludge grass. She lit incense on her counter. Her rainbow striped dress which shows off the rainbow butterfly tattoo on her left breast smells like nag champa.

|

| Alison in her Oakwood neighborhood kitchen |

"I'll have the song down by this week, no problem."

When her weekly shift starts at the Tavern, Alison passes out a song list with over 300 options she knows by heart. No lyrics, no back-up music, just her and a wireless microphone.

In 2001, Alison opened her singing bartender act at Francois' Seafood & Steak House in Kalmazoo. She quickly gained a loyal following singing through a self-operated mic-pack while working both behind the bar and across the restaurant floor. She makes drinks, gets change, writes your order and brings your food all while singing a song requested by the diners.

“I even play instruments back there too. Harmonica, tambourine, shaker. Sort of like a human jukebox. I can actually write words while I’m singing in front of a crowd. I’m singing “Walking After Midnight” and trying to write down chicken pizza. You know? By the end of the first night I had it down. I have this amazing ability to absorb information. I didn’t even know it was a gift. But I probably know lyrics to a thousand songs.”

Several years after opening her act, Alison was let go when Francois’s wife didn’t allow her to claim her tips from credit cards that hadn’t been punched into the machine.

“It was so retarded because I was the best employee. I was the manager on duty, waiting on everybody—servers would stand in the back and talk to each other while I was busting my ass and singing at the same time” she said. “It was two days before Christmas and I just told her I thought it was wrong. And she said ‘I have to make an example out of you.’ And I said ‘well, I don’t think so.’”

|

| The Old Dog Tavern Source: OldDogTavern.com |

The next Wednesday when she would have been singing at Francois’, Alison had a new gig at Nick’s. The place was packed and Francois was empty. Later she went on to Louie’s, then The Strutt and now she has arrived at Old Dog and has been singing under the giant hanging canoe, stuffed moose head and taxidermied weasels for a year and a half.

When the Strutt closed, Alison was sought out by the owner of Old Dog Tavern. Her fans still followed, including her favorite groupie, Mustang Sally, an 87 year-old who woman who sometimes sings along with Alison and accidentally went to Woodstock and hated it.

“It was a natural progression. I’m even singing the same time, same night. Didn’t screw anything up with the regulars. They were like ‘Okay, next week we’ll be over at Old Dog.”

As the only singing bartender on the Westside of Michigan, Alison has found some resistance to her schtick, especially among her fellow bartenders.

“I’ve had girls be really snotty to me and they don’t want to accept me behind the bar. It’s real territorial behind the bar. Most bartenders are that way. But they always kind of fail to figure out that I was bringing in so much business.”

When working at the bar, Alison would split tips with the other waitresses. A fellow bartender who had bullied her apologized years later. After Alison quit, she made $30 on a good night when should would have been making $200 during her act.

“I’m a pretty damn good bartender. I’ve bartended for 23 years. But I’ve been singing my whole life.”

Alison’s childhood was jammed with music. On their first date, her mother and father went to see the Beatles in 1964. They were 14.

“My mom said people were going ape-shit. She would have too but she didn’t want to look silly in front of my dad.”

The window seat in Alison’s living room is brimming with old and new vinyl records, including The Beatles, all in their original cases, siting next to her mother’s old record player.

|

| Alison's vinyl collection |

She got her stage name, Alison Wonderland, after she split from her band “Two Peas and a Blonde.” After she divorced from her husband and dyed her hair brown, she couldn’t keep the old name.

“I picked that name because when I was a little girl my mom and dad took me to go see Alice in Wonderland, and I thought it was two words—I couldn’t read yet. And so I thought her name was Alison Wonderland. I’m not sure if it totally fits who I am now but it did at the time.”

Alison doesn’t think she has any problems in her life. She believes her purpose, more than anything, is to spread joy across the planet, bartending and singing, teaching pilates Monday through Friday and doing good around Kalamazoo.

“I’ve been thinking more about how am I to people, how do I treat people. I feel like we focus too much on jobs. ‘Cause I don’t have a lot of money and I don’t have insurance and I’m raising two teenagers.”

But Alison feels like eventually it will pay off.

“I’m being my authentic self. I’m doing what I love instead of something that I feel obligated to do. And I can do it with a lot of joy and it’s just, I don’t think I have any idea of how being that ripple effect for people comes back to you. It comes back to me in beautiful ways.”

Because of Alison’s desire to spread joy, she has found karma in abundance, from free passes to her favorite shows, being asked to emcee festivals, free beer, free food, a plus one. She puts together random acts of kindness from wiping snow off of a strangers car at the gas station to writing letters on Valentine’s Day and sticking them under windshield wipers.

“It comes in a bunch of different ways, the abundance. Like parking places. I always get front parking places. And I feel like that’s a reward from the universe.”

The fresh cut wildflowers on her kitchen came from along her neighbors' wire fence.

|

| Alison's stolen wildflowers |

Before settling down in Kalamazoo and becoming a figure in the bar-scene, Alison wanted to move to L.A. and become a famous singer. But at 25, things shifted. During the summer Alison worked with her future husband on Mackinaw Island at Mission Point, a college that only lasted for four years.

“He was totally cute and fun. And then I got pregnant. It happened quick.”

“He was like ‘Oh shit. I have to get it together. I have to have a family. I have to make money. And that was it. He just went off into corporate America and wanted to achieve. He wrapped his self worth in achieving and he made money his goal.”

After twelve years of marriage, bartending was Alison’s first real step away from her ex-husband and the kids.

“I stayed because I thought a house at the end of the cul-de-sac with a mini-van, with two adorable children and cable T.V. made you the American dream. And I literally thought if this is the American dream, it is a nightmare for me, and someone needs to wake me up. This is not what I bargained for. I am frickin’ miserable. And then when I chose me, everything just unfolded.”

Now Alison has lived alone for the past five years, sharing custody with her ex-husband.

“I would say every single part of my life is evolving and changing and growing and abundant and full of wealth and happiness and joy. That one piece of him—he’s my biggest teacher. And not the kind of teacher that you love. We’re talking patience and forgiveness and detachment. I get so angry at him. It’s a terrible out of control feeling. But I’m trying to get better at it. He’s my kids’ dad. What’re ya gonna do? Murder him? No. I don’t want to go to jail. Got too much important shit to do. Can’t be screwing around with him. Can’t let him fuck up my life that way. No one has the power to control your life but you. I actually prayed for him today. For him to be happy. To love himself.”

Over a decade later, Alison realizes she put her life on hold for her husband, except for raising the kids. But her lack of degree and experience didn’t stop her. She believes she created her own happiness.

|

| Alison showing off her cigarette girl routine |

“My friends who are working in corporations hate it. They’re fat. They don’t take care of themselves. They don’t have any time to enjoy their kids, to enjoy their life. And they wouldn’t even consider doing anything for themselves. Because that’s too indulgent. They’re doing laundry. Like hell no. I will have five jobs and make it work in my life so that I can still be with my kids and my friends and be happy now.”

People in Kalamazoo feel Alison’s positive vibe. Some have even suggested she run for Mayor someday.

“The truth of the matter is I’m not exactly sure if I want to be the mayor of Kalamazoo but maybe I should just say, the Kalamazoo Ambassador. I like that title better so that I don’t have to know about politics or any of that crap.”

Word Count: 1696

Intended Publication: MLive or Kalamazoo Gazette

Wednesday, May 8, 2013

Profile Writing Reflection

First off, hey classmates. I am so sorry I posted my article so late. Really, very unfair & disrespectful to all of my workshop group. I apologize.

This piece was rough for me, but ended up feeling okay about the draft. It was hard after weeks of writing and re-writing our personal pieces to have to rely on someone else for an interview. My first two options weren't working out, and I was flustered about where to go when everything was falling through.

Interviewing Alison was a really good decision though. I met her three years ago and we haven't kept contact other than the rare occasion I'll see her at a concert at Bell's or an art hop. But I knew she'd be a good interview because of her eagerness to share her stories, she is a story teller, and her way of speaking felt so natural, I knew capturing her voice and inflections would be a fun challenge.

I don't know if the story has enough heft. I think she's interesting, and she has faults and struggles, but not sure if that's enough? I'm interested to know what people think.

In writing the piece, transcribing was the most difficult part for me. I can't remember anything. I have the worst memory, so I had go through the whole interview slowly. And Alison's interview lasted 2.5 hours, so it was dense with lots of anecdotes. Writing my piece so late, I didn't feel like I had time to get into the narrative aspect of the piece—oops, that's the point, right?—and relied on her quotes because they were so strong, the ones I paraphrased may have even been stronger in her words.

I think that's going to be my biggest critique and edits: how do I push this into a more narrative piece? And how do I choose whether to put myself in the work? I wanted to write about finding her at her house stealing flowers from the neighbors garden and how she showed me her tattoo of a panda on her boob on facebook but I couldn't wrap my head around whether that would add or if those were just moments that spoke to me and detracted from the profile.

This piece was rough for me, but ended up feeling okay about the draft. It was hard after weeks of writing and re-writing our personal pieces to have to rely on someone else for an interview. My first two options weren't working out, and I was flustered about where to go when everything was falling through.

Interviewing Alison was a really good decision though. I met her three years ago and we haven't kept contact other than the rare occasion I'll see her at a concert at Bell's or an art hop. But I knew she'd be a good interview because of her eagerness to share her stories, she is a story teller, and her way of speaking felt so natural, I knew capturing her voice and inflections would be a fun challenge.

I don't know if the story has enough heft. I think she's interesting, and she has faults and struggles, but not sure if that's enough? I'm interested to know what people think.

In writing the piece, transcribing was the most difficult part for me. I can't remember anything. I have the worst memory, so I had go through the whole interview slowly. And Alison's interview lasted 2.5 hours, so it was dense with lots of anecdotes. Writing my piece so late, I didn't feel like I had time to get into the narrative aspect of the piece—oops, that's the point, right?—and relied on her quotes because they were so strong, the ones I paraphrased may have even been stronger in her words.

I think that's going to be my biggest critique and edits: how do I push this into a more narrative piece? And how do I choose whether to put myself in the work? I wanted to write about finding her at her house stealing flowers from the neighbors garden and how she showed me her tattoo of a panda on her boob on facebook but I couldn't wrap my head around whether that would add or if those were just moments that spoke to me and detracted from the profile.

Alison Wonderland | Narrative Profile

Alison Cole needs a kazoo. This Wednesday at the Old Dog Tavern in Kalamazoo Michigan, Alison plans to sing and play a solo to Hall & Oats' hit "I Can't Go for That (No Can Do)."

Her old kazoo went missing and she’s hoping to buy a new one, preferably one that says “There really is a Kalamazoo.” She considered where she could find one downtown while eating a tempura shrimp roll with crab on top from D&W. She mixed a heaping soup spoon full of wasabi into her gluten-free soy sauce until it turns the color of March sludge grass. She lit an incense on her counter and her rainbow striped dress which shows off her rainbow butterfly tattoo on her left breast smells like nag champa.

"I'll have the song down by this week, no problem."

When her weekly shift starts at the Tavern, Alison passes out a song list with over 300 options she knows by heart. No lyrics, no back-up music, just her and a wireless microphone.

In 2001, Alison opened her singing bartender act at Francois' Seafood & Steak House in Kalmazoo. She quickly gained a loyal following singing through a self-operated mic-pack while working both behind the bar and across the restaurant floor. She makes drinks, gets change, writes your order and brings your food all while singing a song requested by the diners.

“I even play instruments back there too. Harmonica, tambourine, shaker. Sort of like a human jukebox. I can actually write words while I’m singing in front of a crowd. I’m singing “Walking After Midnight” and trying to write down chicken pizza. You know? By the end of the first night I had it down. I have this amazing ability to absorb information. I didn’t even know it was a gift. But I probably know lyrics to a thousand songs.”

Several years after opening her act, Alison was let go when Francois’s wife didn’t allow her to claim her tips from credit cards that hadn’t been punched into the machine.

“It was so retarded because I was the best employee. I was the manager on duty, waiting on everybody—servers would stand in the back and talk to each other while I was busting my ass and singing at the same time” she said. “It was two days before Christmas and I just told her I thought it was wrong. And she said ‘I have to make an example out of you.’ And I said ‘well, I don’t think so.’”

The next Wednesday when she would have been singing at Francois’, Alison had a new gig at Nick’s. The place was packed and Francois was empty. Later she went on to Louie’s, then The Strutt and now she has arrived at Old Dog and has been singing under the giant hanging canoe, stuffed moose head and taxidermied weasels for a year and a half.

When the Strutt closed, Alison was sought out by the owner of Old Dog Tavern. Her fans still followed, including her favorite groupie, Mustang Sally, an 87 year-old who woman who sometimes sings along with Alison and accidentally went to Woodstock and hated it.

“It was a natural progression. I’m even singing the same time, same night. Didn’t screw anything up with the regulars. They were like ‘Okay, next week we’ll be over at Old Dog.”

As the only singing bartender on the Westside of Michigan, Alison has found some resistance to her schtick, especially among her fellow bartenders.

“I’ve had girls be really snotty to me and they don’t want to accept me behind the bar. It’s real territorial behind the bar. Most bartenders are that way. But they always kind of fail to figure out that I was bringing in so much business.”

When working at the bar, Alison would split tips with the other waitresses. A fellow bartender who had bullied her apologized years later, siting that after Alison quit, she made $30 on a good night when should would have been making $200 during her act.

“I’m a pretty damn good bartender. I’ve bartended for 23 years. But I’ve been singing my whole life.”

Alison’s childhood was jammed with music. On their first date, her mother and father went to see the Beatles in 1964. They were 14.

“My mom said people were going ape-shit. She would have too but she didn’t want to look silly in front of my dad.”

The window seat in Alison’s living room is brimming with old and new records, including The Beatles, all in their original cases, siting next to her mother’s old record player.

“My mom used to listen to record players when I was a kid on vinyl. I’d watch Annie, and I wanted to be Annie. And the Wizard of Oz was the first song I ever sang, ‘Over the Rainbow.’ And I just wanted to be her, them.”

She got her stage name, Alison Wonderland, after she split from her band “Two Peas and a Blonde.” After she divorced from her husband and died her hair brown, she couldn’t keep the old name.

“I picked that name because when I was a little girl my mom and dad took me to go see Alice in Wonderland, and I thought it was two words—I couldn’t read yet. And so I thought her name was Alison Wonderland. I’m not sure if it totally fits who I am now but it did at the time.”

Alison doesn’t think she has any problems in her life. She believes her purpose, more than anything, is to spread joy across the planet, bartending and singing, teaching pilates Monday through Friday and doing good around Kalamazoo.

“I’ve been thinking more about how am I to people, how do I treat people. I feel like we focus too much on jobs. ‘Cause I don’t have a lot of money and I don’t have insurance and I’m raising two teenagers.”

But Alison feels like eventually it will pay off.

“I’m being my authentic self. I’m doing what I love instead of something that I feel obligated to do. And I can do it with a lot of joy and it’s just, I don’t think I have any idea of how being that ripple effect for people comes back to you. It comes back to me in beautiful ways.”

Because of Alison’s desire spread joy, she has found karma in abundance, from free passes to her favorite shows, being asked to emcee festivals, free beer, free food, a plus one. She puts together random acts of kindness from wiping snow off of a strangers car at the gas station to writing letters on Valentine’s Day and sticking them under windshield wipers.

“It comes in a bunch of different ways, the abundance. Like parking places. I always get front parking places. And I feel like that’s a reward from the universe.”

Before settling down in Kalamazoo and becoming a figure in the bar-scene, Alison wanted to move to L.A. and become a famous singer. But at 25, things shifted. During the summer Alison worked with her future husband on Mackinaw Island at Mission Point, a college that only lasted for four years.

“He was totally cute and fun. And then I got pregnant. It happened quick.”

“He was like ‘Oh shit. I have to get it together. I have to have a family. I have to make money. And that was it. He just went off into corporate America and wanted to achieve. He wrapped his self worth in achieving and he made money his goal.”

After twelve years of marriage, bartending was Alison’s first real step away from her ex-husband and the kids.

“I stayed because I thought a house at the end of the cul-de-sac with a mini-van, with two adorable children and cable T.V. made you the American dream. And I literally thought if this is the American dream, it is a nightmare for me, and someone needs to wake me up. This is not what I bargained for. I am frickin’ miserable. And then when I chose me, everything just unfolded.”

Now Alison has lived alone for the past five years, sharing custody with her ex-husband.

“I would say every single part of my life is evolving and changing and growing and abundant and full of wealth and happiness and joy. That one piece of him—he’s my biggest teacher. And not the kind of teacher that you love. We’re talking patience and forgiveness and detachment. I get so angry at him. It’s a terrible out of control feeling. But I’m trying to get better at it. He’s my kids’ dad. What’re ya gonna do? Murder him? No. I don’t want to go to jail. Got too much important shit to do. Can’t be screwing around with him. Can’t let him fuck up my life that way. No one has the power to control your life but you. I actually prayed for him today. For him to be happy. To love himself.”

Over a decade later, Alison realizes she put her life on hold for her husband, except for raising the kids. But her lack of degree and experience didn’t stop her. She believes she created her own happiness.

“My friends who are woking in corporations hate it. They’re fat. They don’t take care of themselves. They don’t have any time to enjoy their kids, to enjoy their life. And they wouldn’t even consider doing anything for themselves. Because that’s too indulgent. They’re doing laundry. Like hell no. I will have five jobs and make it work in my life so that I can still be with my kids and my friends and be happy now.”

People in Kalamazoo feel Alison’s positive vibe. Some have even suggested she run for Mayor someday.

“The truth of the matter is I’m not exactly sure if I want to be the mayor of Kalamazoo but maybe I should just say, the Kalamazoo Ambassador. I like that title better so that I don’t have to know about politics or any of that crap.”

Word Count: 1696

Intended Publication: MLive or Kalamazoo Gazette

Word Count: 1696

Intended Publication: MLive or Kalamazoo Gazette

Wednesday, May 1, 2013

Telling True Stories, Barry, Talese & MacFarquhar | Reading Response

This section of Telling True Stories made me reflect on my experience as both an English major and an AnSo minor. Over the past four years I've often felt tension when in an English class because—in class at least—we don't approach a text from an anthropological perspective, and vice-versa in an AnSo class, where the writing is dull and unapproachable. It seems that through reporting, and especially narrative or ethnographic journalism, both artful writing and ethical, in-depth observation are required. "The writers here all report with their heads, their hearts, and their deep practicality" (Kramer, 20). This personal participation, like the reporter who worked as a corrections officer at a prison to get a story, seems both valiant and off to me. The reporting across cultures essay by Victor Merina was so short and succinct. I wanted more about the problematics and ethical tensions that arrise when trying to capture the narratives of an individual from another culture. All of the sections on crossing boundaries seemed overly simplistic.

This made me think about something Marin mentioned in class briefly, accelerated intimacy. When I got to the chapter by Wilkerson in Telling, I was psyched to learn more. I think that's my biggest draw to journalism, narrative and creative non, that opportunity for intimacy with a stranger, in both a not-creepy and creepy way. Maybe it's my obsession with food metaphors, but I liked the image of that under-skin layer of the green onion, a part you only use if you have to because you haven't gone deep enough. But the power dynamic that Wilkerson brushed over did make me pause. If it's guided intimacy, forced comfort, it feels manipulative, but I'm beginning to see it as a skill set, not as conniving.

Reading the two profiles from Barry and Talese and MacFarquhar's piece on New Yorker profiles made me think about the medium or the form of pieces. I loved reading about Frank Sinatra's comeback and cold, but scrolling down a never ending page made me lose interest. I think the New York Times consistently does a great job with breaking up text by having a piece on numerous pages or having images along the left-hand side as you scroll. I was more invested in Sinatra before reading the piece, but because of the snippy sentences and quick breaks, I was quickly won over by Mr. Zinsser.

One topic in Telling True Stories that I've been mulling over and would like to discuss in class is the idea of finding a 'universal truth' in your piece. I think this week with the third re-write of our personal pieces, I finally recognized that that was a major aspect of my piece where I was lacking. Hopefully I established some universal truths in a more solid way.

This made me think about something Marin mentioned in class briefly, accelerated intimacy. When I got to the chapter by Wilkerson in Telling, I was psyched to learn more. I think that's my biggest draw to journalism, narrative and creative non, that opportunity for intimacy with a stranger, in both a not-creepy and creepy way. Maybe it's my obsession with food metaphors, but I liked the image of that under-skin layer of the green onion, a part you only use if you have to because you haven't gone deep enough. But the power dynamic that Wilkerson brushed over did make me pause. If it's guided intimacy, forced comfort, it feels manipulative, but I'm beginning to see it as a skill set, not as conniving.

Reading the two profiles from Barry and Talese and MacFarquhar's piece on New Yorker profiles made me think about the medium or the form of pieces. I loved reading about Frank Sinatra's comeback and cold, but scrolling down a never ending page made me lose interest. I think the New York Times consistently does a great job with breaking up text by having a piece on numerous pages or having images along the left-hand side as you scroll. I was more invested in Sinatra before reading the piece, but because of the snippy sentences and quick breaks, I was quickly won over by Mr. Zinsser.

One topic in Telling True Stories that I've been mulling over and would like to discuss in class is the idea of finding a 'universal truth' in your piece. I think this week with the third re-write of our personal pieces, I finally recognized that that was a major aspect of my piece where I was lacking. Hopefully I established some universal truths in a more solid way.

Monday, April 29, 2013

The Saudi Marathon Man | Narrative vs. News

|

| Source: The New Yorker, by Emmanuel Dunand/AFP/Getty. |

Last week I mentioned this piece in class when Zac brought up the question of when to use narrative journalism. Re-reading the piece, I still believe this is a strong example of combining timely news writing with a narrative edge and tone. Maybe it could work as a strong example for our third project. Either way it's a great read.

How to Poach an Egg | Third Revision

Home-making is not my forté. I’ve left the stove on overnight, exploded dishes in the microwave, let carrots fester in the fridge. I dump my clean laundry on my bed so that I will fold it, and instead fall asleep on top of my already crinkled shirts. I take after my father’s side of the family, the ones who throw out milk a week before it expires, who prefer take-out over farmer’s markets, who sniff their clothes to see if they’re clean.

I’ve worried this lack of domesticity has distanced me from my mother’s side, especially my grandmother, Grandy. I’ve assumed the trait has slowly sifted out of the Seiverson line—if home-making activities are something I’d like to pursue, it’s in my blood, but needs to be unearthed. I lean towards arts instead of craft. But Grandy’s got it in her genes, which she hang dries in the basement then irons on a small Ikea fold out on her bed. She makes me want to learn to quilt. She is the archetype, the mother figure, the caretaker. When I was still a kid, I used to spend the night at her old place on the Mississippi and we’d watch “The Little Rascals” and sing about pickles and dollars.

In the morning we’d wake up to barely browning english muffin toast—this magical hybrid, airy like Thomas’ but not dense and chewy—and eggs fried quickly in too much butter. Sometimes she whipped up coveted egg-in-a-basket, a small window cut in a slice of bread with the bottom of a juice glass, the perfect frying hole for a small egg. Sleepovers at Grandy’s were the only times I would eat breakfast. My own mother would force me to drink Carnation Breakfast Essentials, a disgusting ‘chocolate’ protein ‘shake’ that tasted like saw dust and cold Swiss Miss.

But I could stomach Grandy’s eggs. They didn’t have the cold, soggy-ness I had associated with breakfast. They warmed me, got me going. I began cooking eggs on my own. Julia Child taught be how to make a French omelet—it’s in the wrists—I found I like my scrambled eggs barely cooked, as cloud-like as possible.

Grandy is oddly egg-like, actually. Taupe-y, almost. She has a lot of beige and white in her aesthetic, the kind of blue button-up wearing woman who still has my great-grandmother’s sewing kit equipped with thimbles in her bedroom closet.

Because of those lazy mornings at Grandy’s, I’ve grown this infatuation with eggs. I love them, actually. Their off-ness, the way they roll on a counter, the way they ooze and crackle in a pan, how they thicken or poof a dish. Eggs are cheap meal, they can be decorated, pickled or thrown. But I had never learned how to make the most beautiful of eggs, a perfect boiled parcel of gooey-goodness: a poached egg. Eating them feels rich, decadent, covered in hollandaise or cooked in a homemade tomato sauce.

I told myself the simplicity makes dropping eggs into boiling water so difficult. You can find tricks and secret techniques all over the internet, but none of them seemed to work. The number of eggs I wasted, yolks bursting in bubbling water, egg whites turning into a bland egg-drop soup, has to be at least two dozen.

If I wanted to make the perfect egg, I knew who I had to call.

“Oh Han, I’m flattered you’d ask me.” Grandy said. “It’s easy, Sweety, come over on Saturday and I’ll show you.”

We stood in her kitchen, surrounded by heart-shaped black and grey stones she had collected on the Mississippi and on the shores of Lake Superior. Her spatulas are heart-shaped. She has framed drawings her mother made in the 30s—my great grandmother drew the fashion designs for Vogue before cameras were commercialized. I never knew my great-grandmother. She had died very young, when Grandy was only nine. On the counter we gathered a small, 2 quart pan and filled it halfway with water, a tablespoon of vinegar, a slotted spoon, some salt and two slices of english muffin bread. We were listening to Etta James.

“You’ve got to get the water just barely boiling,” Grandy said, pouring the vinegar into the pot. “Bubbling up the sides. It can’t be too hot or they will break.”

“Did your mother ever teach you how to cook Grandy? Was she a good cook?”

“Oh, she was a beautiful cook. Everything she did was beautiful—she was an artist. And she cooked like one. The day she died she left meat out, defrosting on the counter.”

A few months before my Mom had told me Grandy was writing an essay on her mother’s death and how it had affected her life. At twenty I still didn’t know my family history beyond two generations.

“Grandy, will you tell me about her?”

As the water heated up, when it was just right, she swirled the pan slightly with her wrist so that the liquid spun in a circle.

“I don’t know much, Han. I was so little. So, so little. She made all my clothes—she loved sewing. I hated it. I wanted the clothes from the store, but all mine had perfect little buttons and pockets.”

“But how did she die?”

She tapped the egg on the edge of the counter, held the cracked vessel over the pan, pushed her fingers through the shell, and lowered the gloppy mass into the eye of the tornado.

“She left a note one afternoon. I was at girl-scouts. When I got home, my father was on the steps. He told me the neighbors had invited me over for dinner. It was like she disappeared, it never felt like she died.”

If your egg looks awful at this point, like an old man with a beard floating on his back, you’re doing it right.

“In her note she said she couldn’t be the wife and mother she ‘ought to be.’” Grandy said. “I didn’t know any of this until much, much later, when I was 16 and my step mother died suddenly, when I put the pieces together.”

Poaching takes patience. As the filmy strands of egg become opaque and less flimsy, gather the whites with the slotted spoon and tuck them loosely around the yolk.

I watched how Grandy made the egg into a neat little bundle with ease. On cue the bread popped up from the toaster.

“She was before her time, Hannah. You couldn’t do this. You couldn’t make eggs and be an artist.”

She handed me the butter for the toast.

“You had to choose. She wasn’t domestic enough. Wasn’t a mother enough. Cared about her own art more than her children.”

She set the poached egg on its toast bed.

“Of course now we know that’s not true. She just wanted more than she was given. She wanted to get out.”

I salted and cracked pepper on the tops of both the eggs. We sat down at the dinning room table. It was before noon and the sun was just reaching the tops of the Minneapolis skyline.

“Thank you for telling me, Grandy”

“I could’ve told you sooner. We should know these things about each other. Share ourselves.”

She lifted the butter knife over our breakfast, and sliced, letting all the insides out.

Word Count: 1232

Intended Publication: Lives

How To Poach an Egg Franklin Outline

Complication:

- Hannah experiences disconnect

Development

- Hannah seeks Grandy

- Grandy teaches Hannah

- Hannah gleans truth

Resolution

- Hannah connects

Wednesday, April 24, 2013

Writing for Story | In Response

This book reminded me of my Dad. At first I thought the book was too outdated and was surprised it was a part of our reading material. I thought about how journalism shifts so rapidly; advice from 1985 seems ancient. But after Franklin told us about his childhood as the ringleader of a white gang—whaaaaat?—and I got over my initial distate for his prescriptive writing, I realized his voice sounded similar to that of my father's, who worked as a newspaper sports writer from his college and high school years in the late seventies and eventually became an investigative reporter for Kare 11 News in Minnesota.

In high school I was drawn to journalism because of his work in the field. I liked the idea of really investigating a piece, of getting to draw out the details to make a story more tense, to get the scoop. But as I veered toward fiction and poetry, I stuck my nose up at my dad's notes on 'integrity' and 'craft' and 'true' story-telling.

I found myself rolling my eyes in the same way I roll them at my dad reading Franklin's advice to future writers. But then moments of relevance continued to pop up for me. The tension between writing as art and writing as craft is one that has always struck me, and Franklin's love of the short story kept me interested. In "The New School for Writers" he described his love of the form that "demanded the utmost of the writer, both technically and artistically. Yet the shortness of the story—the same thing that made it so difficult—was also its saving grace" (Franklin, 22).

I thought his diatribe about not being able to find valuable lessons in 'how to write books' books ironic as he opened the first section, but as soon as he began writing I bit my tongue. His piece "Mrs. Kelly's Monster" got me. Not telling us whether she died at the end, his use of the ‘pop pop pop repeating.

Wednesday, April 17, 2013

How to Poach an Egg Etcetera | Personal Essay Revision

I’ve got this casual infatuation with eggs. I love them, actually. Their off-ness, the way they roll on a counter, the way they ooze and crackle in a pan, how they thicken or poof a dish. Eggs are cheap meal, they can be decorated, pickled or thrown. But I had never learned how to make the most beautiful of eggs, a perfect boiled parcel of gooey-goodness: a poached egg. Eating them feels rich, decadent, covered in hollandaise or cooked in a homemade tomato sauce.

Last summer on a trip home to Minneapolis, I called up my go-to egg aficionado, my mother’s mother, Grandy. She’s oddly egg-like, actually. Taupe-y, almost. She has a lot of beige and white in her aesthetic, the kind of blue button-up wearing woman who still has my great-grandmother’s sewing kit equipped with thimbles in her bedroom closet. She’s always been the most domestic of my family members. My mother loves to cook and entertain and vacuums and windex-es before the cleaning lady shows up. Myself, I dabble in organizing rooms, folding fitted sheets and making pasta salads, but Grandy—she is the archetype, the mother figure. I’ve always assumed the trait has slowly sifted out of the Seiverson line, that if home-making activities are something I’d like to pursue, it’s in my blood, but needs to be excavated.

Grandy’s got it in her genes, which she hang dries in the basement then irons on a small Ikea fold out on her bed. She makes me want to learn to quilt. When I was still a kid, I used to spend the night at her old place on the Mississippi and we’d watch “The Little Rascals” and sing about pickles and dollars.

|

| Source | Andrew Filer, Flickr |

In the morning we’d wake up to barely browning english muffin toast—this magical hybrid, airy like Thomas’ but not dense and chewy—and eggs fried quickly in too much butter. Sometimes she whipped up coveted egg-in-a-basket, a small window cut out in the toast with the bottom of a juice glass, the perfect frying hole for a small egg. Sleepovers at Grandy’s were the only times I would eat breakfast. My own mother would force me to drink Carnation Breakfast Essentials, a disgusting ‘chocolate’ protein ‘shake’ that tasted like saw dust and cold Swiss Miss.

“Mom, this stuff makes me gag. I’m going to barf all over the bus and no one will talk to me.”

“Well, Hun, we’ll just have to home-school you until you start eating real breakfast.”

But I could stomach Grandy’s eggs. They didn’t have the cold, soggy features I had associated with breakfast. They warmed me, got me going. I began cooking eggs on my own. Julia Child taught be how to make a French omelet—it’s in the wrists—I found I like my scrambled eggs barely cooked, as cloud-like as possible. I made the Barefoot Contessa’s quiche Lorainne, which, let’s be honest, contains mostly cream, not eggs. But I suck at poaching an egg.

I told myself the simplicity makes dropping eggs into boiling water so difficult. You can find tricks and secret techniques all over the internet, but none of them seemed to work. The number of eggs I wasted, yolks bursting in bubbling water, egg whites turning into a bland egg-drop soup, has to be at least two dozen.

Grandy had the answer.

“Oh Han, I’m flattered you’d ask me. It’s easy, Sweety, come over on Saturday and I’ll show you.”

We stood in her kitchen, surrounded by heart-shaped black and grey stones she had collected on the Mississippi and on the shores of Lake Superior. Her spatulas a heart-shaped. She has framed drawings her mother made in the 30s—my great grandmother drew the fashion designs for Vogue before cameras were commercialized. I never knew my great-grandmother. She had died very young, when Grandy was only nine. On the counter we gathered a small, 2 quart pan and filled it halfway with water, a tablespoon of vinegar, a slotted spoon, some salt and two slices of english muffin bread. We were listening to Etta James.

|

| One of my many failed attempts at poaching |

“You’ve got to get the water just barely boiling,” Grandy said, pouring the vinegar into the pot. “Bubbling up the sides. It can’t be too hot or they will break.”

“Did your mother ever teach you how to cook Grandy? Was she a good cook?”

“Oh, she was a beautiful cook. Everything she did was beautiful—she was an artist. And she cooked like one. The day she died she left meat out, defrosting on the counter.”

A few months before my Mom had told me Grandy was writing an essay on her mother’s death and how it had affected her life. At twenty I still didn’t know my family history beyond two generations.

“Grandy, will you tell me about her?”

As the water heated up, when it was just right, she swirled the pan slightly with her wrist so that the liquid spun in a circle.

“I don’t know much, Han. I was so little. So, so little. She made all my clothes—she loved sewing. I hated it. I wanted the clothes from the store, but all mine had perfect little buttons and pockets.”

“But how did she die?”

She tapped the egg on the edge of the counter, held the cracked vessel over the pan, pushed her fingers through the shell, and lowered the gloppy mass into the eye of the tornado.

“She left a note one afternoon. I was at girl-scouts. When I got home, my father was on the steps. He told me the neighbors had invited me over for dinner. It was like she disappeared, it never felt like she died.”

If your egg looks awful at this point, like an old man with a beard floating on his back, you’re doing it right.

“In her note she said she couldn’t be the wife and mother she ‘ought to be.’” Grandy said. “I didn’t know any of this until much, much later, when I was 16 and my step mother died suddenly, when I put the pieces together.”

Poaching takes patience. As the filmy strands of egg become opaque and less flimsy, gather the whites with the slotted spoon and tuck them loosely around the yolk.

I watched how Grandy made the egg into a neat little bundle with ease. On cue the bread popped up from the toaster.

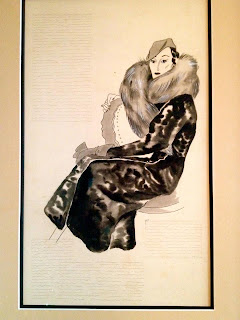

|

| A drawing for Vogue by my Great Granmother |

“She was before her time, Hannah. You couldn’t do this. You couldn’t make eggs and be an artist.”

She handed me the butter for the toast.

“You had to choose. She wasn’t domestic enough. Wasn’t a mother enough. Cared about her own art more than her children.”

She set the poached egg on its toast bed.

“Of course now we know that’s not true. She just wanted more than she was given. She wanted to get out.”

I salted and cracked pepper on the tops of both the eggs. We sat down at the dinning room table. It was before noon and the sun was just reaching the tops of the Minneapolis skyline.

“Thank you for telling me, Grandy”

“I could’ve told you sooner. We should know these things about each other. Share ourselves.”

She lifted the butter knife over our breakfast, and sliced, letting all the insides out.

The American Man at Age Ten by Susan Orlean | In Response

Before reading her piece, I knew I would like Susan Orlean's work. As soon as I read her brief bio and the phrase "I like writing about streets," I felt like I got her. I also loved how Orlean talked about walking and noted she “dawdles with enthusiasm,” which is something I tend to do myself. I think that's one of the aspects of narrative journalism I want to embrace and but that also makes me uneasy. I like the transparency that comes with journalism. There is nearly always a byline on every piece and you can easily dig through a writer's work and see their opinions and biases, which can be a hinderance or an asset.

Before delving into the piece, I loved the playfulness of Orlean’s title and lead. The irony in the break in the title, placing American Man and his age on the second line made me smile, and the odd opening of imagining Orlean’s marrying her ten-year-old subject successfully drew me into the piece. In my modernism and postmodernism class last quarter we talked a lot about the use of lists in post/post-post modernist work and so now I always notice them and Orlean’s repetition of ‘We’ was comical and just fun. I liked how in the first section it seemed like she could be generalizing about any “American” ten-year-old boy—which means a heteronormative, white, middle class boy—but then went into detail about Colin’s particularities.

Orlean’s piece, while sweet and sometimes sentimental in her observation of Colin, is also a social commentary through the perspective of a fifth grader. In such a short space Orlean’s is able to touch on race, gender, death, HIV/AIDS, abortion, and violence. She makes assumptions about who the children surrounding Colin will grow up to be, both with positive and negative outcomes. The comments the boys made about their classmates, especially the girls, frightened me but did not surprise me with their hateful and sometimes violent tone. This recent piece in Jezebel about two fifth graders arrested last month after conspiring to rape and kill a female classmate definitely came to mind.

When the piece shifted to a statistical nature, I was glad Orlean moved into the studies. She rarely spoke from the I throughout the piece, and definitely showed and did not tell her perspective on young boys and gender development, but her stance quickly became obvious, especially with the subtle yet powerful image of her trapped with the dog in the dark, tangled in Colin's fishing line.

One problematic issue I’ve been dealing with recently as a writer and reader came up for me this week while reading. Over the past two years I’ve struggled to find male writers who’s work I enjoy reading. I think it stems from my women, gender and sexuality studies which has made it difficult for me to read without a feminist lens or critique. Last week, while I thought the readings were helpful in terms of craft, I did not enjoy the majority of the speakers. This piece, because of its theme, tone and perspective captivated me in a way others do not. I'm conflicted because I do not think the gender identities of authors makes them intrinsically good or bad for me to read, but it's a pattern I've seen developing among the books I choose to read and blogs I follow. I'm curious to know if anyone else in class has had a similar experience.

Monday, April 8, 2013

How to Poach an Egg

I’ve got this casual infatuation with eggs. I love them, actually. Their off-ness, the way they roll on a counter, the way they ooze and crackle in a pan, how they can thicken or poof a dish. They’re a cheap meal, they can be decorated, pickled or thrown. But I had never learned how to make the most beautiful of eggs, a perfect parcel of gooey-goodness: a poached egg. Poached eggs are like truffles to me. They are a rare treat, only for special occasions. Eating them feels rich, decadent, covered in hollandaise or cooked in a homemade tomato sauce.

Last summer on a trip home to Minneapolis, I called up my go-to egg aficionado, my mother’s mother, Grandy. She’s oddly egg-like, actually. Taupe-y, almost. She has a lot of beige and white in her aesthetic, the kind of blue button-up wearing woman who has throw blankets all over the house and still has my great-grandmother’s sewing kit equipped with thimbles in her bedroom closet. I used to spend the night at her old place on the Mississippi when I was little and we’d watch “The Little Rascals” and sing about pickles and dollars. But on cue, five minutes in, Grandy began to slump on the couch, snoring, mumbling in her sleep.

In the morning we’d wake up to barely browning english muffin toast—this magical hybrid, airy like Thomas’ but not dense and chewy—and eggs fried quickly in too much butter with coarse salt and pepper. Sometimes she whipped up coveted egg-in-a-basket, a small window cut out in the toast with the bottom of a juice glass, the perfect frying hole for a small egg. Sleepovers at Grandy’s were the only times I would eat breakfast. My own mother would force me to drink Carnation Breakfast Essentials, a disgusting ‘chocolate’ protein ‘shake’ that tasted like saw dust and cold Swiss Miss.

“Mom, this stuff makes me gag. I’m going to barf all over the bus and no one will talk to me.”

“Well, Hun, we’ll just have to home-school you until you start eating real breakfast.”

I would dump the full glasses down the toilet or in my mom’s flower garden depending on how vengeful I felt.

But I could stomach Grandy’s eggs. They didn’t have the cold, soggy features I had associated with breakfast. They warmed me, got me going. I began cooking eggs on my own. Julia Child taught be how to make a French omelet—it’s in the wrists—I found I like my scrambled eggs barely cooked, as cloud-like as possible. I know how to tell when a zucchini frittata is browned but not overcooked. I made the Barefoot Contessa’s quiche Lorainne, which, let’s be honest, contains mostly cream, not eggs. But I suck at poaching an egg.

I told myself the simplicity makes dropping eggs into boiling water so difficult. You can find tricks and secret techniques all over the internet, but none of them seemed to work. The number of eggs I wasted, yolks bursting in bubbling water, egg whites turning into a bland egg-drop soup, has to be at least two dozen.

Grandy had the answer.

“Oh Han, I’m flattered you’d ask me. It’s easy, Sweety, come over on Saturday and I’ll show you.”

We stood in her kitchen, surrounded by heart-shaped black and grey stones she had collected on the Mississippi and on the shores of Lake Superior. Her spatulas a heart-shaped. She has framed drawings her mother made in the 30s—my great grandmother drew the fashion designs for Vogue before cameras were commercialized. I never knew my great-grandmother. She had died very young, when Grandy was only nine. On the counter we gathered a small, 2 quart pan and filled it halfway with water, a tablespoon of vinegar, a slotted spoon, some salt and two slices of english muffin bread. We were listening to Etta James.

“You’ve got to get the water just barely boiling,” Grandy said, pouring the vinegar into the pot. “Bubbling up the sides. It can’t be too hot or they will break.”

“Did your mother ever teach you how to cook Grandy? Was she a good cook?”

“Oh, she was a beautiful cook. Everything she did was beautiful—she was an artist. And she cooked like one. The day she died she left meat out, defrosting on the counter.”

A few months before my Mom had told me Grandy was writing an essay on her mother’s death and how it had affected her life. At twenty I still didn’t know my family history beyond two generations.

“Grandy, will you tell me about her?”

As the water heated up, when it was just right, she swirled the pan slightly with her wrist so that the liquid spun in a circle.

“I don’t know much, Han. I was so little. So, so little. She made all my clothes—she loved sewing. I hated it. I wanted the clothes from the store, but all mine had perfect little buttons and pockets.”

“But how did she die?”

She tapped the egg on the edge of the counter, held the cracked vessel over the pan, pushed her fingers through the shell, and lowered the gloppy mass into the eye of the tornado.

“She left a note one afternoon. I was at girl-scouts. When I got home, my father was on the steps. He told me the neighbors had invited me over for dinner. It was like she disappeared, it never felt like she died.”

If your egg looks awful at this point, like an old man with a beard floating on his back, you’re doing it right.

“In her note she said she couldn’t be the wife and mother she ‘ought to be.’” Grandy said. “I didn’t know any of this until much, much later, when I was 16 and my step mother died suddenly, when I put the pieces together.”

Poaching takes patience. As the filmy strands of egg become opaque and less flimsy, gather the whites with the slotted spoon and tuck them loosely around the yolk.

I watched how Grandy made the egg into a neat little bundle with ease. On cue the bread popped up from the toaster.

“She was before her time, Hannah. You couldn’t do this. You couldn’t make eggs and be an artist.”

She handed me the butter for the toast.

She handed me the butter for the toast.

“You had to choose. She wasn’t domestic enough. Wasn’t a mother enough. Cared about her own art more than her children.”

She set the poached egg on its toast bed.

“Of course now we know that’s not true. She just wanted more than she was given. She wanted to get out.”

I salted and cracked pepper on the tops of both the eggs. We sat down at the dinning room table. It was before noon and the sun was just reaching the tops of the Minneapolis skyline.

“Thank you for telling me, Grandy”

“I could’ve told you sooner. We should know these things about each other. Share ourselves.”

She lifted the butter knife over our breakfast, and sliced, letting all the insides out.

Intended Publication: New York Times Magazine | Lives

Word Count: 1214

Wednesday, April 3, 2013

Maurice Sendak, Inspiration and Storytelling

Just testing out the blog, but also wanted to post this video. When talking about our favorite profiles in class, I immediately thought of this interview between Maurice Sendak, author of Where the Wild Things Are—who The New York Times called the "most important children’s book artist of the 20th century,"—from several months before he died. This video is just a brief clip of the interview—which you can find in it's entirety here,—but like the illustrator of the clip I too was driving around aimlessly when the Fresh Air story came on the radio and stuck with me more than any profile piece I can remember. They were supposed to be discussing Sendak's new book, but Gross and Sendak quickly transitioned to talking about life, writing and all the leaving that comes with dying. If you like to laugh while sobbing, this one's for you.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)